Published: October 21, 2020

Written by: Peter Hayes

For the last few years I have undertaken critical research into practices and assumptions around early or “precocious” puberty. Children with early puberty, particularly girls, are sometimes given drugs to prevent further pubertal development. My research challenges the ethics and effectiveness of treating children in this way. Early puberty is also said to occur relatively frequently amongst internationally adopted children. My research questions the accuracy of this claim.

This research is interdisciplinary. It is informed by the distinction between science and ideology, a central concern of political theory. It draws on sociological theories of medicalisation, feminist critiques of gendered social concerns and questionable social norms, and legal concepts of child rights. It also involves engaging with and contributing to the medical literature, and as such requires knowledge of how the incidence of early puberty and its treatment has been framed and investigated in mainstream medical research.

The medical background to the research can be dated to the 1980s when a new and supposedly highly effective class of drugs, Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone agonists (GnRHas) were first trialled on children with early puberty. The use of these drugs to stop early puberty has now extended worldwide. Also in the 1980s, the hypothesis was advanced that internationally adopted children had a high incidence of early puberty. This hypothesis became widely accepted after studies of children adopted into Sweden, Denmark, Belgium and Spain appeared to corroborate it.

There has been occasional criticism of the overuse of GnRHa treatment for early puberty in the medical literature. Most criticism of GnRHas, however, has come from outside the medical profession amongst patients who have been prescribed the drugs for various medical conditions. Such criticisms are becoming increasingly visible online.

Systematic scholarly criticism of GnRHa treatment of early puberty has developed only in the last few years with the pioneering work of Professor Celia Roberts. Prior to my research, there was no systematic criticism of the hypothesis that internationally adopted children had a high incidence of early puberty in the medical or other scholarly literature.

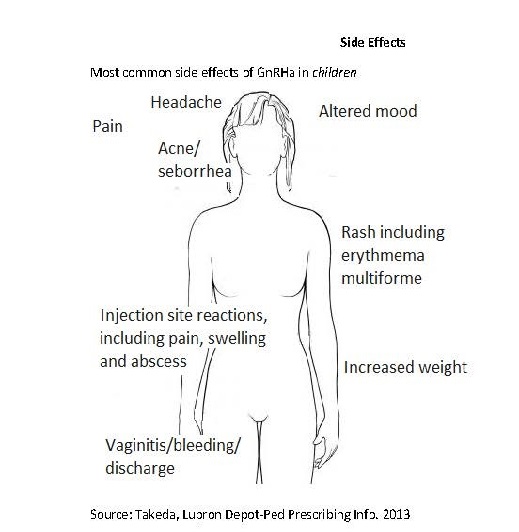

The question of whether it is appropriate to give drugs to children who mature unusually early but who are not unhealthy raises important ethical issues. The drugs have side effects; the purposes behind the treatment are open to question; treatment potentially infringes children’s rights to bodily and mental integrity and to unimpeded physical development. The question of whether internationally adopted children really have a high incidence of early puberty is also important because these children may be singled out for scrutiny and treatment. Further, if internationally adopted children do not, in fact, have a high incidence of early puberty, then a fundamental misconception has been built into scientific accounts of pubertal timing.

My initial research, published in a medical journal, argued that the apparently high incidence of early puberty in internationally adopted children was in fact due to these children having an under-recorded age. This argument was developed through critical scrutiny of the existing research evidence, including the finding that there was a high incidence of early puberty amongst children adopted at an older age, but not amongst those adopted as infants. This finding, I argued, was to be expected if age was under-recorded, as the older the child at the time of adoption, the greater the possibility that their chronological age was significantly older than their recorded age.

This theoretical research was followed-up by more practical research undertaken with Professor Tony Tan. The supposedly high incidence of early puberty in internationally adopted children had been interpreted as evidence that catch-up growth following early deprivation triggered pubertal onset. It follows that if deprived children available for adoption have dates of birth that are reasonably accurate, then after these children have been adopted the catch-up explanation predicts a high incidence of early puberty, where the under-recorded age explanation does not. Girls adopted from China in the 1990s and early 2000s provide a critical test of these different theories: their birth records are reasonably accurate, and at the time of adoption most of them were underweight. Using menarcheal age as a marker of puberty we found no evidence of a high incidence rate of early menarche amongst 814 such girls adopted from China. Eventually, this research too was published in a medical journal.

The question of the appropriateness of treating healthy children with early puberty has been pursued through critical scrutiny of the medical literature on the topic. This research has found continuing claims in this literature that the drugs are effective in increasing final height despite the contrary evidence of randomised control trials. It has found that drugs have been used to try and increase final height of girls with a predicted adult height that is not particularly short; that children are typically treated for several years until they reach the mean age of pubertal onset rather than treatment being stopped as soon as they fall within a normal range; that there is an almost complete lack of discussion in the medical literature about how children with early puberty might be supported rather than medicated; that the increased risk of sexual abuse for children with early puberty has been overstated; that children are being medicated on the basis of statistical projections of an increased likelihood of delinquent or “risky” behaviour, and that even though a 2001 finding reported that children’s IQ was significantly reduced after two years of treatment, numerous subsequent studies into GnRHa treatment have failed to measure if it impacts on IQ. A critique of the GnRHa treatment of girls that addressed all of these issues was published in a women’s studies journal.

This latter article has been cited in a medical article that concerns the impact of GnRHas on cognitive function. The more general critique of GnRHa treatment in the women’s studies article has been extensively cited in a book which critically investigates the science of puberty from a Foucauldian perspective. The research into internationally adopted children has had the greatest impact. Three studies: in the USA, in Romania, and in Italy, have now been published that cite this research work and which provide cautious corroboration of the theory that internationally adopted children do not, in fact, have a high incidence of early puberty.

Dr Peter Hayes is a Programme Leader for BA Politics and History and Subject Leader for Politics in the Combined Subjects programme. He has undertaken research into Political Theory and Ideology, including work on Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, Karl Marx, Karl Popper and Joseph Conrad. And also applied his research interests in ideology to areas that include Adoption Policy, East Asian Politics, and to the History and Philosophy of Science and Medicine. Learn more about Peter Hayes in his staff profile.